ALFRED A. YEE

Perspective: Constuction Law

KENNETH R. KUPCHAK

Kenneth Kupchak is a director at the law firm of Damon Key Leong Kupchak Hastert in Honolulu. He represented Alfred Yee and several of his businesses from 1971 until Yee passed away in 2017.

Al was one of the most remarkable persons that I have ever met. He was always gracious, genuine, friendly, positive, congenial, humble, and grounded, which first became apparent during my very first meeting with Al in the late summer of 1971. Al had called his Yale schoolmate, Frank Damon, about a patent licensing agreement. Frank sent me. As I waited in Al’s firm’s reception area, I noticed a book on a table, titled “Everything That I Know About Structural Engineering,” by Alfred Alphonse Yee. Having never met the man, I grabbed it for clues. When I opened the book, however, I discovered that every page was blank—lesson one.

Ever experience the woven tube known as the Chinese finger trap? Aware of this from childhood, Al designed a splice sleeve to bind rebar in high-rise columns that allowed the Ala Moana Building to be constructed one floor every two days—at the time an unheard of speed. It was this patent that we licensed to Nisso-Master Builders in 1971 just as countries in Asia began to build UP!

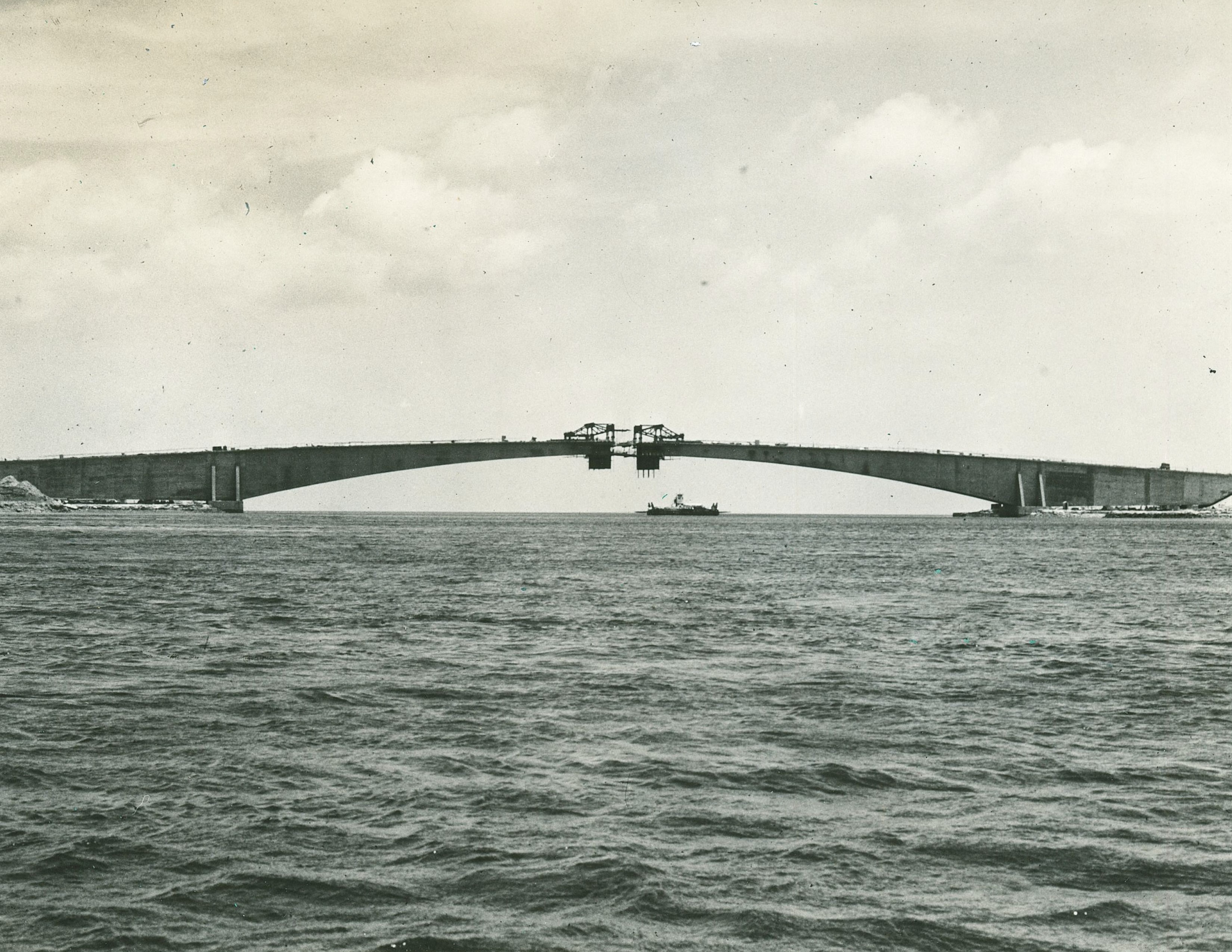

Over the years Al designed many structures, including in 1976 the 1,700-foot-long, cantilevered, Babaledoup to Korror Bridge in Palau. The dual-segmented bridge was the second longest of its kind in the world, though it met a tragic end. Al designed the bridge to be in tension, with tendons to support each of the two 750-foot cantilevered arms. As concrete is a continuous chemical process, the material’s creep had caused a reverse speed bump to occur at the center hinge. Although the “bump” did not detract from the bridge’s structural integrity, the government of Palau decided to “remedy” the bump. Unfortunately, the task went to a new team, which revised the structural concept, squeezing each of the cantilevered arms and causing the middle of the bridge to rise, changing the structural scheme to compression.

Ever experience the woven tube known as the Chinese finger trap? Aware of this from childhood, Al designed a splice sleeve to bind rebar in high-rise columns that allowed the Ala Moana Building to be constructed one floor every two days—at the time an unheard of speed. It was this patent that we licensed to Nisso-Master Builders in 1971 just as countries in Asia began to build UP!

Over the years Al designed many structures, including in 1976 the 1,700-foot-long, cantilevered, Babaledoup to Korror Bridge in Palau. The dual-segmented bridge was the second longest of its kind in the world, though it met a tragic end. Al designed the bridge to be in tension, with tendons to support each of the two 750-foot cantilevered arms. As concrete is a continuous chemical process, the material’s creep had caused a reverse speed bump to occur at the center hinge. Although the “bump” did not detract from the bridge’s structural integrity, the government of Palau decided to “remedy” the bump. Unfortunately, the task went to a new team, which revised the structural concept, squeezing each of the cantilevered arms and causing the middle of the bridge to rise, changing the structural scheme to compression.

Photo Credit: Unknown

Apparently, the induced forces could not be absorbed by the concrete matrix, packed with those tendons. The whole thing delaminated in less than half an hour, about 30 days after the retrofit. It resulted in seven deaths. When Al and I arrived in Palau, we were taken to dinner by the governor and his head of infrastructure. The retrofit team eventually paid around $20 million to Palau. Al, to nobody’s surprise, won on summary judgment against the retrofit team’s attempt to seek contribution.

Al had a knack for seeing simple solutions where others saw complex problems. In addition to the splice sleeve, Al designed concrete barges, which may still be operating in the Philippines—floating docks capable of handling the largest ocean-going tankers, while also serving as the world’s largest oil tank farm to be floated off Indonesia.

Al turned developer, by necessity. The energy crisis of 1974 stopped work overnight. (At the time, fuel accounted for 60 percent of the cost of concrete.) Nothing new would appear on designers’ drawing boards for some years. Wanting to keep his team together, Guam became the source of self-generated engineering work Al noticed an abandoned WWII airfield, Harmon Field, and converted it into a light industrial, wholesale, retail, and labor housing “park.” He also formed limited partnerships to acquire leases in Tumon, which later became Guam’s resort destination, and Mangilao, where the University of Guam is located.

Al was conscious of passive design, developing an innovative way to keep the Ala Moana Building cool: The windows are semi shielded by vertical louvers that run up the building, which rotate with the sun, admitting indirect light—a rare but ingenious idea at the time.

Speaking of that office building, I was seated in the conference room for a meeting with Al in 1975 when a 7.5 earthquake hit Akaka Falls on the Big Island, 300 miles away. The building started to sway. We were on the 8th floor, and I was looking for a place to hide. Al just smiled. “Not to worry,” he said. “We designed this building.” I then wondered why the conference table wasn’t moving. He said, “Look underneath.” It was bolted to the floor.

Al turned developer, by necessity. The energy crisis of 1974 stopped work overnight. (At the time, fuel accounted for 60 percent of the cost of concrete.) Nothing new would appear on designers’ drawing boards for some years. Wanting to keep his team together, Guam became the source of self-generated engineering work Al noticed an abandoned WWII airfield, Harmon Field, and converted it into a light industrial, wholesale, retail, and labor housing “park.” He also formed limited partnerships to acquire leases in Tumon, which later became Guam’s resort destination, and Mangilao, where the University of Guam is located.

Al was conscious of passive design, developing an innovative way to keep the Ala Moana Building cool: The windows are semi shielded by vertical louvers that run up the building, which rotate with the sun, admitting indirect light—a rare but ingenious idea at the time.

Speaking of that office building, I was seated in the conference room for a meeting with Al in 1975 when a 7.5 earthquake hit Akaka Falls on the Big Island, 300 miles away. The building started to sway. We were on the 8th floor, and I was looking for a place to hide. Al just smiled. “Not to worry,” he said. “We designed this building.” I then wondered why the conference table wasn’t moving. He said, “Look underneath.” It was bolted to the floor.